“Do I really need to read all this philosophy?”

Sep 12th, 2012 | By Marc Applebaum | Category: Human ScienceThe students who put this question to me are usually taking their first course in phenomenological or hermeneutic (narrative) psychological research. And in a way, I feel for them, because many of them didn’t expect to be facing something called “epistemology,” and bumping into any number of arcane Greek terms that seem to bear no relationship to the psychological phenomena they are interested in studying, like trauma and resilience, creativity, or leadership.

The problem, as I see it, is that many of us assume that “trauma,” “creativity,” or “narrative” are real things in the same way as the Lincoln Memorial is a real thing. In other words: “Just point to it, it’s obvious, it’s right there!” Or even worse: “I know it when I see it!”

All too often when students encounter words like “resilience” in the media, and even in many psychology textbooks, these words—which are theoretical constructs—are used to mistakenly convey the sense that the constructs are real, self-evident “things” that are already present in the world—rather than the provisional creations of science. In other words, these constructs are reified in everyday language, and in too much “psychological” language as well—exemplifying what philosophers have identified—sorry—as “the fallacy of misplaced concreteness”!

All too often when students encounter words like “resilience” in the media, and even in many psychology textbooks, these words—which are theoretical constructs—are used to mistakenly convey the sense that the constructs are real, self-evident “things” that are already present in the world—rather than the provisional creations of science. In other words, these constructs are reified in everyday language, and in too much “psychological” language as well—exemplifying what philosophers have identified—sorry—as “the fallacy of misplaced concreteness”!

In other words, a beginning student would assume that psychologists are all in agreement about what “resilience” means. But on the contrary, my students are usually surprised to discover, as soon as they begin to review the literature, that there is not a strong consensus regarding psychological constructs such as “resilience.” Instead, these terms are usually highly contested—if we’re lucky, because that means the arguments and different points of view are well-articulated—or more often, such terms are used in highly divergent ways (without those differences being carefully reckoned with).

Back to “the fallacy of misplaced concreteness.” The fact that we have to go back to philosophy to properly name the problem is exactly my point. It’s philosophy, after all, that teaches us how to think critically. More than that, the fundamental questions of how we as researchers know what we know are philosophical, not psychological: these philosophical questions are propaedeutic (preparatory, foundational) for psychological inquiry.

In other words any vision of psychology that is not a purely instrumental one requires that we wrestle with epistemological issues—so that, to do genuine research, meaning to engage in authentic scientific inquiry rather than adopting a cookbook approach—means grasping the epistemological assumptions underlying the method we have chosen to use. These observations are not original on my part, nor are they uniquely phenomenological—though the phenomenological tradition has its own unique ways of encountering and articulating them.

But back to our initial problem—why we need to engage with philosophy via epistemology, and why we tend to fall for the fallacy of misplaced concreteness? I’ll claim that this is due largely to the overwhelming success of the positivist vision of psychology, because this vision lends itself to the fallacious reading. How so? In 1923 Edwin G. Boring, one of the most important historians of American empirical psychology, wrote about intelligence tests in the New Republic. Regarding the meaning of the construct “intelligence,” he famously said this:

But back to our initial problem—why we need to engage with philosophy via epistemology, and why we tend to fall for the fallacy of misplaced concreteness? I’ll claim that this is due largely to the overwhelming success of the positivist vision of psychology, because this vision lends itself to the fallacious reading. How so? In 1923 Edwin G. Boring, one of the most important historians of American empirical psychology, wrote about intelligence tests in the New Republic. Regarding the meaning of the construct “intelligence,” he famously said this:

“Intelligence is what the tests test. This is a narrow definition, but it is the only point of departure for a rigorous discussion of the tests. It would be better if the psychologists could have used some other and more technical term, since the ordinary connotation of intelligence is much broader. The damage is done, however, and no harm need result if we but remember that measurable intelligence is simply what the tests of intelligence test, until further scientific observation allows us to extend the definition.”

To be generous, we can imagine that Boring is reminding us in a modest way that experimental psychology is not measuring the everyday lived-meanings of intelligence (what he refers to as the “ordinary connotations”), but instead we are simply measuring against our measure. On the other hand, one can imagine centuries of philosophers rising in protest from their graves at Boring’s exercise in circular reasoning, a striking example of psychology as a Procrustean bed: whatever the lived-meanings of intelligence may be, for psychology as an empirical science, intelligence can only be defined within the limits of those constructs that lend themselves to measurement.

For those of us who teach and study at Saybrook, as inheritors of the existential-humanistic tradition underlying the founding of our institution, one might say we have a unique responsibility to think through our epistemologies, since ours is a minority approach within psychological science. And this requires us to think through our implicit philosophical assumptions, and to encounter philosophy as a means of reflecting critically about the meaning and purpose of our work.

Reference and notes

Boring, E. (1923). Intelligence as the tests test it. New Republic. 33, 35-37.

Lincoln Memorial photo credit: Stuck in Customs via photo pin cc

Studying photo credit: Pragmagraphr via photo pin cc

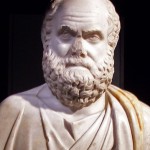

Socrates photo credit: Sebastià Giralt via photopin cc

The Greek vase depicts Theseus killing Procrustes

Follow

Follow email

email

Thank you for this, Marc. I feel strongly that those of us doing clinical work need to continually reconsider and investigate our terms, as the context in which the terms are used changes continually. Over the years I have struggled through my brushes with philosophy and epistemology. It has helped my clinical practice immensely in that I am able to distinguish between people I am treating, even though their diagnosis may be the same. In other words, my ability to discern has increased and this is essential for clinicians to be able to meet people where they are at.

Nice post, Marc. If only our concepts could arise out of our lived experience! Speaking of which, Al Johnstone said that Husserl used ‘nonsymbolic, nonlinguistic, non cultural concepts’ in order to describe intersubjectivity as a lived experience. If that is true, it must be because lived experience allows us to formulate such concepts out of itself, if the right phenomenological method is followed.

Thank you Peter! I see that this issue of ‘nonsymbolic, nonlinguistic, non cultural concepts’ is addressed in the concluding chapter of your book, “Layers in Husserl’s Phenomonology: On Meaning and Intersubjectivity”. I need to read your book! It’s a difficult and important question I think. Probably my hermeneutically-inclined friends would be jumping out of their chairs at the very idea of (at least) “nonlinguistic concepts”! But I need to better understand what Johnstone means by that phrase.

I’m sure you saw that in my presentation at ICNAP I was trying to describe some palpable differences between varying ways of relating to lived-experiences, when we narrate what we’ve lived (something that happens mostly but not exclusively linguistically). For example, I think there is an indisputable difference, psychologically, between speaking “from” a lived-experience and merely speaking “about” a lived experience. I don’t mean the distinction is absolute, but in clinical psychology it is well understood that we can observe the difference between a person being in living contact with the experience they’re relating, versus being cut off from the lived experience, or superimposing a possibly ill-fitting interpretation upon an experience.

But I am cautious about using the word “pure” to describe absolutely any psychological phenomena! For me, increasingly, psychology is the human science of the humanly “messy”! As much as I love clear conceptual distinctions, psyche is so multilayered that multiple meanings and possibilities are nearly always present, and we’re so plunged in contingency, that any fixed binary opposition seems unlikely to hold up.

That being said, my own sense of phenomenological psychology’s mission (for example, as expressed in Giorgi’s 1970 book, “Psychology as a Human Science”) is to clear a space free from theory-laden approaches to psyche so that the life of psyche can be described as it presents itself. My argument in the ICNAP presentation was that I think we’re free to do so, provided that we contextualize our descriptions by acknowledging the hermeneutic community and interests within which our describing is taking place.

Thanks for your contributions!

Marc

Yes, the nonlinguistic idea is strange. And to be honest I am not sure quite what Johnstone had in mind. To me it seems to mean that concepts are prelinguistic in the sense that experience founds language while it also responds to it and thus sometimes concepts can arise out of experience that are not simply reducible to analytic language games or practices, etc. I take these kind of concepts to be partaking in the meaning of being in its existential structures and not simply in a method of description. But perhaps that is just totalizing hopefulness?

I did very much like your ICNAP presentation, and I learned a lot about what I need to read–Giorgi for one, Appelbaum for another! Thanks for this blog. I really hope it continues!