Interview: Elsaesser on communicating with coma patients

Jul 3rd, 2012 | By Marc Applebaum | Category: Feature Sebastian Elsaesser is a psychotherapist specializing in process work, psychosomatic medicine, and altered states of consciousness. He maintains an active practice in Stuttgart, Germany and in Brazil. For years he has collaborated with Peter Frör in developing a program in the Intensive Care Units of Klinikum der Universität München, one of Germany’s most technically sophisticated hospitals. There, Elsaesser and Frör train caregivers in a unique skill—reaching out communicatively to patients in coma. In May 2012 I interviewed Elsaesser in Istanbul. Elsaesser’s work is intensely descriptive in the phenomenological sense of paying extraordinary attention to the way in which the other (the coma patient) is present, noting one’s own presence in the situation, and also a deeply hermeneutical process as the caregiver seeks to correctly “read” faint signs from the other, who is in coma. –Marc Applebaum

Sebastian Elsaesser is a psychotherapist specializing in process work, psychosomatic medicine, and altered states of consciousness. He maintains an active practice in Stuttgart, Germany and in Brazil. For years he has collaborated with Peter Frör in developing a program in the Intensive Care Units of Klinikum der Universität München, one of Germany’s most technically sophisticated hospitals. There, Elsaesser and Frör train caregivers in a unique skill—reaching out communicatively to patients in coma. In May 2012 I interviewed Elsaesser in Istanbul. Elsaesser’s work is intensely descriptive in the phenomenological sense of paying extraordinary attention to the way in which the other (the coma patient) is present, noting one’s own presence in the situation, and also a deeply hermeneutical process as the caregiver seeks to correctly “read” faint signs from the other, who is in coma. –Marc Applebaum

Elsaesser: This work began when I was asked by Peter Frör, a Protestant priest who works in one of the most technologically advanced hospitals in Germany, with thirteen intensive care units, to explore how to work with coma patients in these units. Because the people working in these units to support patients or family members were helpless. Priests, by law in Germany, can go to all these places that have restricted access, like prisons and hospitals. And in the intensive care units they were in a way helpless about what to do, because their task with the patients is not one of speaking, and so usually they were “used” by the medical staff or nurses only to talk to the patients’ relatives…

Applebaum: Because the patients themselves don’t speak…

Elsaesser: Yes. But there is a very basic theme that Peter and I took seriously, that is Biblical: “You have been ill, and I visited you”; not visited your family—I visit you. (Elsaesser is paraphrasing the New Testament, Matthew 25:35, “I was a stranger and you made me welcome; naked and you clothed me, sick and you visited me, in prison and you came to see me.”) So it is an active approach: nobody asks if the person themself is visited, and people think he’s just a vegetable, or he’s just “gone”…“Oh, you don’t need to go there [to vist him in the hospital], he’s just there [in a coma].”

Applebaum: The usual idea is that you don’t need to visit such people because they are comatose?

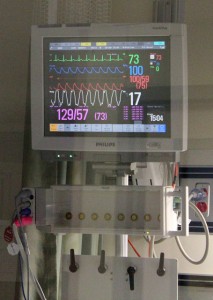

Elsaesser: Yes, because these are patients in coma or very remote states of consciousness…[but our idea is different] so we visit  these people. And I think it is very important; fifty years ago this intensive care unit was started, and these people—and if you pass the threshold, you can become aware—that 90% of the people there would not live without the machinery. So you are in fact entering a different space, you could say “Death’s threshold”. So you are there—and what now?

these people. And I think it is very important; fifty years ago this intensive care unit was started, and these people—and if you pass the threshold, you can become aware—that 90% of the people there would not live without the machinery. So you are in fact entering a different space, you could say “Death’s threshold”. So you are there—and what now?

People are used to relating in speech, and they want to connect in speech. And if this is not there, they say, “OK, leave them alone…they are stressed anyway.” But we have had very clear experiences—we know, after fifteen years of work—that these people, they need contact. It is not just contact with clergy—they need contact itself…and usually the only contact they get is needles, interventions, and so on.

And of course there was the myth that they are not aware at all. Of course they are not aware in the usual sense; however, it makes a difference for them if you are there with them. The idea is not that we go there to heal them, or to get them back, but rather to be with them. In fact my effort is to go where they are, instead of getting them to be where I am. Usually the family wants them to be like they were before. And this is a big difference: I can come there and say, “Oh, it is important where they are.”

Applebaum: In other words, your only aim is to relate to the state that the patient is in today?

Elsaesser: Yes. So the first thing is to appreciate where they are.

Applebaum: And what does that “appreciating” imply for you?

Elsaesser: First of all that this is a meaningful state that they are in…even if it is transitory. And you can say that one way of looking at the coma—if it is spontaneous and not actually medically-induced–and even then sometimes—it is sometimes a state of indecision, being “between the worlds.” So it’s a very special state of being—it is a “dreamland”. And usually they are abandoned by others in their lives. They should either come back, or die.

Mainly people want that they will come back. Now we begin to appreciate that which is–with all its radical complications. Like you have an accident…the person was there, and suddenly he’s there on an entirely different level. And they have not chosen to be there in the sense of a conscious choice: they are thrown into something that they don’t know, so it’s like going into an unknown land. So myself, I need to be ready to undergo a voyage, to travel into this unknown land.

Applebaum: This raises many questions…for example, it sounds as if you have the sense that you are joining with the patient in a way—how do you validate that? How can you establish contact with the other in a way that confirms for you that the contact isn’t only your imagination, but is a shared perception? You’d mentioned that it makes a difference to the patient whether they’re visited or not—how can you tell? How can you observe this?

Elsaesser: Well after you say, “I am going to visit the person,” it’s a very different approach than psychotherapy, or the work of a Priest, in a sense, because it is your initiative. Like in psychotherapy you receive the client, but it is his choice to come. Here, it is my initiative, not the patient’s. This is a very different approach—that I go there.

Then, when I am clear about my intention, the next question is, “how do I establish contact?” So one thing is the language of the coma is the body. The body “speaks”—even if a person is seemingly or really completely out of contact, the body speaks, as long as somebody is breathing even with the help of a machine, the body speaks.

So in medical science they would say, “Oh, these movements are only reflexes.” But we noticed very quickly…like if I say to the person, “Hello, here I am”, say my name even, say the name of the person—“Haaaah!…” (he makes a breathing noise)—the breathing of the patient might change! So this is already a response—the change of the breath—so one of the things is, you have to learn to pay attention to all the signals of the body, because there are small modifications happening, there might be a small movement of the eyebrows. Sometimes this is not the case right away—in our experience, you have to stay, sometimes at least twenty minutes, until contact might be established.

So you might be there for a time, and you experiment, and you might even think “it doesn’t work,” so you have to go through your frustration, because it is a harder mirror—you don’t know, you simply don’t know what will occur. But the body speaks in many small signals. This is one thing…then you might get in contact, physically in contact, touching the person, and there is a whole schooling in how to do this. And people say, “Oh, this should not be done! You don’t know if they want the contact!” But do you know whether they want a medical intervention? It’s done anyway…

Applebaum: In other words there is already ongoing manipulation of the coma patient’s body in physical therapy…

Elsaesser: Yes, very hard manipulations are done in examinations, very tough stuff is done, so you see the question that is often asked, the ethical question, is whether if I give the patient my hand, whether this contact is wanted…

Applebaum: holding the person’s hand…

Elsaesser: Holding the hand. But you don’t question it when they get stuff like medical instruments inserted into the body…

Applebaum: Feeding tubes…

Elsaesser: Feeding tubes and cruel things—and you say, “it’s necessary for the person’s survival”…

Elsaesser: Feeding tubes and cruel things—and you say, “it’s necessary for the person’s survival”…

Applebaum: So the contact we take for granted is something like the person’s body being treated almost as an object?

Elsaesser: Yes, and so I relate in a very different way, I relate to the person, to the soul…and of course you go slowly, step by step. So you initiate physical contact, and you listen, like if you give your hand to the patient, what comes in response? And there, after some time, usually, something happens.

And for a person in these remote states, a small movement like a finger might be a big world. So you slow down, you go “out of time”, because they have a different sense of time and space. So it is a whole procedure which depends of course…you listen to the body’s signals, you also feel what you feel…you have to refine your own instrument as a body yourself, and then you relate body to body. And then there is a dialogue from body to body… it can also be in silence, and of course you also say words, and you feel how they are received. In the beginning you don’t know—of course you don’t know. Its like attempts to speak into the dark…

Applebaum: So reaching out to the other is open and explorative?

Elsaesser: It is an intervention with a great deal of respect, and at the same time, your initiative to go further, and of course people are in different states, sometimes they are only in dream states, and you don’t know who you are for them, because you know their perception is different. Of course we have studied carefully what they say afterwards…

Applebaum: People who have recovered from comas?

Elsaesser: Yes, people who have come out—and there are hundreds of reports, and I will give you only some, or one…for example the person afterwards says, “You know, I was lost in the sea, and I heard your voice, and this was like a light in the sea, and with that, I new where I am, I suddenly noticed ‘I’m alive!’”—something like this. Or it could be that after recovering from coma the patient says to the person who has visited them during the coma, “I know you!”

Applebaum: Has this happened?

Elsaesser: Yes! They sometimes say, “You are living in my community?”

Applebaum: Has this happened to you?

Elsaesser: It happened to Peter Frör …”You live in my community?” The patient said. And then it turns out that the person thinks that Peter is very familiar, but it is like a dream knowing—it is like, “I know you!” but the attribution of the context for knowing the other is not…

Applebaum: Empirically accurate?

Elsaesser: Yes. It is like a dream…but somehow it creates a relationship that is important and meaningful. So you don’t know exactly who you represent for the patient…sometimes you might even represent the Secret Service, because they feel persecuted! It can be many things…you know in the United States in fact what happened was that while we did this work with coma patients, the medical scientists also did research, “Oh we have to find out how the patients experienced the intensive care unit,” and there have been studies done, because they thought, “Well, they might suffer afterwards because they are more physically disabled,” like they lose some faculties that they had before, so the scientists wanted to conduct studies.

But the first time the medical scientists conducted interviews to see how the patients felt, there were big surprises in the results:  one surprise was, the fact that some people couldn’t walk afterwards after recovering from the coma was hard but not traumatic, but they often felt traumatized about how they had been treated while in the coma: nightmares, post-traumatic stress that they were violated, that they had medieval procedures done to them, that they had been torn apart, put into pieces, that they experienced that the machines were living beings, demons, all of this. And this stayed with them: they cannot walk, but the problem is that they feel traumatized more than physically disabled. Part of this has to do with the fact that there was no contact during the coma, nobody was there to say “Hello, you are here, its great that you’re breathing!”

one surprise was, the fact that some people couldn’t walk afterwards after recovering from the coma was hard but not traumatic, but they often felt traumatized about how they had been treated while in the coma: nightmares, post-traumatic stress that they were violated, that they had medieval procedures done to them, that they had been torn apart, put into pieces, that they experienced that the machines were living beings, demons, all of this. And this stayed with them: they cannot walk, but the problem is that they feel traumatized more than physically disabled. Part of this has to do with the fact that there was no contact during the coma, nobody was there to say “Hello, you are here, its great that you’re breathing!”

Applebaum: So afterwards there was a sense of alienation or having been treated as a thing?

Elsaesser: Yes, so it is an existential theme. People are, as you said, in a way feeling treated like objects. And because they are, on the intensive care unit, basically without clothes—completely exposed, without any protection, and sometimes they need really for somebody else to have the courage to relate. And some family members do this, very intuitively. Say, the mother of a child who says, “I am with you! You are my love!” And this is very important.

Applebaum: So there has been research done with patients who had been accompanied during the coma and later recovered

Elsaesser: Yes, though that is not the focus of our research, but of course we’ve observed, and we accompany the people through several stages when its possible. But of course we are directly with the patient and sometimes without any goal. Just being with them, and you see this is the interesting thing, I even support the clergymen who visit coma patients by saying, “You are very privileged because you have no function.”

Because they say, “I come here and I am useless!” I say, “This is your gift, that you are useless!” because the medical doctors are very busy, they sit behind the monitors, they are constantly looking toward the survival of the patient, and the nurses, they have more patient contact, but the work is more and more stressful, so they are more taken up by the demands of medically monitoring the coma patients. But then people come who have nothing to do. And they feel useless!

And then I say—“This is your gift, that you are not within the medical hierarchy, and you can convey the human side.” And people feel it. Its like with children, people in coma can feel how your intentions are, even if you speak differently. And you see the hypothesis—even if they don’t consciously know what happened, that your way of presence makes a difference if you touch someone where they are.

So this is contact, and contact makes a difference. So that is one level, and then there is a whole technical approach how you work—I only give the example of getting in touch, getting in touch with the breath. So there is one approach in which you get in touch with the patient through attention to their breathing, and you can also get in touch with your own breath, with the breath of the other person, and small alterations, and depending on the state, you can observe if they react, and if they have movements in response.

And you can also possibly sometimes establish “yes” and “no” contact, because they cannot speak, but you can see if you notice that they are somehow really aware, or at least “dreamlike aware”, you can say to the person “Can you do that again?” And they do it again. And you can say, “OK, if you do this, it is a ‘yes.’” So you can start this kind of communication, you know in a general way we “travel” between very different states…the basis is, you’re here, and the first level is survival. They are there in the intensive care unit for survival. But some people do not really want to live, so one of the things you get in contact with is that you get in contact about their will to live or not to live. That is a very big step.

Applebaum: So you have had the experience that you can establish contact at not just a primary level, or an even more subtle level of connection you mentioned related to breathing, but also on a more existential level, you can get a sense of the person’s desire to be alive, or lack of that desire?

Elsaesser: Yes, this is one of the stages of the work. Of course this doesn’t occur right away and this isn’t always possible. I see it as one of the responsibilities, if I accompany this person, that I should also be in tune with the other professions, the medical sciences. They are there to secure survival, and they are there for that side of the situation. It is very important that we are supporting that side also, but not only focused on bare survival.

This has priority, and if the priest only comes in, is only called, when the person dies—this is also a cultural pattern—we had to work through that so that no, we come to celebrate the life of the patient while they are still alive. And so you see when this work gets intensified, also they [the medical providers] get interested, “Oh, what did you find out? How is the person?” Because sometimes they don’t know, the medical people themselves, what the Hell is going on—they are honest about it—what is going on? We don’t know…does it work?

Applebaum: The doctors?

Elsaesser: Yes! For example, they perform a liver transplant, does the person take it? If not, what is missing? As I mentioned, we have discovered a lot of like “laws” or “rules of thumb” that sometimes a person in a very difficult situation only survives if somebody believes in them or wants them to be alive.

Applebaum: Meaning that you found empirically, for example with liver transplant patients’ survival rates that the success rate is statistically significantly, measurably higher for people who have visitors who care about them?

Elsaesser: Yes, who really care about them. We have many examples of this. You know, think if you are in a completely hopeless state, why should you care to survive? Some people want to survive because they have a child, so “I want to survive for my child,” you know these are very common things. But sometimes it is also the opposite, of course. One has to be very careful about it also, sometimes people want to leave the situation, “I don’t want to be with my family anymore.” So I’m very much in favor of the support of family and friends, but sometimes a person is also in the state of, “Oh no, I can’t take being at home any more.”

Elsaesser: Yes, who really care about them. We have many examples of this. You know, think if you are in a completely hopeless state, why should you care to survive? Some people want to survive because they have a child, so “I want to survive for my child,” you know these are very common things. But sometimes it is also the opposite, of course. One has to be very careful about it also, sometimes people want to leave the situation, “I don’t want to be with my family anymore.” So I’m very much in favor of the support of family and friends, but sometimes a person is also in the state of, “Oh no, I can’t take being at home any more.”

Applebaum: When you’re dealing with patients who can’t speak directly, have you or those care-givers you’re working with ever had the experience of getting what for you is a message of “no” from the patient in response to the offer of contact?

Elsaesser: Yes, yes. You see, the work is “feedback oriented.” And of course many of the people we teach are shy—usually I see the cultural bias is, “they [the patients] might not want contact.” The pastors, usually they might think it’s a religious imposition. The people who want to work there, its usually not a religious [motivation], we want you to pray or whatever, instead it is a relational [motivation]. It isn’t something like, “We want you to pray” or whatever…it’s a relationship. The prayer is relationship, hmm? And of course you can have the experience that they want the contact and then suddenly they don’t want it anymore. This shows best if there is no feedback anymore. Negative feedback is no feedback. If there is like a tendency to move away…

Applebaum: For the patient to physically pull away from the other?

Elsaesser: Yes, very small, we don’t consider this to be negative feedback; you might have done the wrong intervention. No feedback is definite [in other words, grasped as a definitive “no” from the other]. So of course in the beginning you have no feedback, so after you’ve had feedback, you can also feel this if you touch a person and there is a counter response…

Applebaum: Some movement?

Elsaesser: Some movement, something subliminal and of course you have to learn this. And sometimes the person goes off…it doesn’t need to mean physically it might be like this [Elsaesser models a physical touch that suddenly becomes disengaged, in a felt way] and you notice, aha!—they don’t want to be with you in that way, in that moment.

Applebaum: Is that something like: you’re feeling contact with the other, and then you feel the contact drop on the other side?

Elsaesser: Exactly. Very good: contact drops. And then you have to be careful, what is what does it mean, that contact drop? You might have touched sensitive ground…you know its only intensified what we experience in everyday life—it’s a magnifying glass—this is what makes it so existential and beautiful, because it is no bullshit, there is no more convention, and this is why I can also behave unconventionally. It is needed. And of course I should be ready also to say: “it is good to be alone.”

It is the same thing with people who are dying—some want to be dying with all the friends and family around, and some people, like for example I’ve seen an instance of a man whose wife was there all the time, all the time with him, but one moment she has to go pee, and the person dies while the wife is peeing—and “Ahhh!” [he simulates a gasp] “I did something wrong!” No: the man wanted to die alone. And you see it’s very different if you have contact and also allow solitude in the contact. It’s very different from abandoning the person.

Applebaum: The felt sense of leaving someone to be alone is phenomenally different from abandoning the person—it’s a different experience, relationally?

Elsaesser: Yes. And I guess what happens in intensive care units, people are relationally abandoned. And this is why this work, which is quite new, makes such an impact. Because it appreciates also a different state like something culturally we don’t have so much, like when you say in the normal state of consciousness, “I want to retreat for a moment,” and usually this means you have to go in your room and be alone. And we have no culture of saying. “Oh, I want to retreat, let’s be silent, I want to be on my own here, together.” And I can still be on my own. And if you honor that, it’s a fantastic experience, you know? And this also you can do there.

Applebaum: So this is something like accompanying the other, without placing a demand on the other?

Elsaessar: Yes. So this is one chapter of it, and for me it was very astonishing because I have worked with indigenous people, within the practice of indigenous shamanism, and people in intensive care units in the middle of the highest technology, have similar experiences spontaneously. Like I told you before, this feeling that they are torn apart, cut into pieces [experiences which are reported by those undergoing experiences in traditional shamanistic practices]. So what happens in intensive care units is extreme—it is highly rational, there is a high level of care because of the medical science, they are 100% reliable, they are much more alert than in usual life, so there exists in a way no “night,” they are always present…

Applebaum: There is always technological vigilance…

Elsaessar: Yes, which has its own power—you see I feel this is very touching, like a person in the intensive care unit has to be examined in a different place because they cannot bring all of the equipment there, so they have to plan it, with batteries, so they move out and they can only be aware one hour, with the machinery but mobile, so they get in an elevator and there is a technician there in case the elevator is blocked they need to repair it right away because otherwise the person dies. There are maybe twenty people involved to secure it.

This is a very powerful thing, and an existential thing—and the people who work there are aware of it, they deal with this, so I think this is a great contribution, I admire this, I think its very important, when you do this work not to be at a distance from the medical side of treatment. At the same time, the people have experiences that are archaic, the patients, they have experiences…and then people say they are just…nuts! But its very archaic, its like as in archaic societies, so you have both here together, And I guess that this has to be honored too, the human experience in extreme states: and if you are not taken care of [during the coma], then it is like a horror trip.

Applebaum: You see the experiential correspondences between what coma patients and those in shamanic cultures undergo, since you have worked in both contexts yourself, and you see the commonalities in the accounts of patients who recover from coma?

Elsaesser: Yes. And you know of course when you’re there you don’t know it, but somehow it is transmitted…and if you are scared of these kinds of experiences, they get excluded…the system usually does this, “Let’s give more medication if we feel they are having difficulties….” As a person who is with them, it is important that I can appreciate these kinds of extreme states in some way that transmits security to them also.

Applebaum: Would you say that part of being with the patient in coma is self-observation?

Elsaesser: Yes, The whole training is in fact basically how to learn how can I be a more refined instrument of perception and observation, and perceive what I provoke with my actions, and again observe my reactions within myself. So as we go there in an unknown land, of course one needs to have some guidelines for learning how to do it, otherwise it seems to be “intuitive” [in the sense of immediately and spontaneously given to the practitioner without training]…but its not.

So the first thing is really learning to read signals in the other, but at the same time you have to be in tune very much with your own responses, so in fact you become the instrument of perception and the techniques are just another aspect that helps that you are in tune with yourself as an instrument. So we developed a teaching process that you become aware of one focus of your consciousness, then another focus, then another, and they pile up until you integrate them. I will name a few; one is the sense of, “I visit you.” It’s very important that you are conscious of the sense that “I visit you.”

Applebaum: As one’s intention for being there with the patient?

Elsaesser: Yes, so its not that I stumble in somewhere, it is that I visit you: very profound. And I visit you means also that I want to get in touch with where you are. So then, “establish contact.” How do I do it? So it can be a focus: how do I get in contact? To focus on that and just with that is a lot. And then a later focus is then “how do I intervene?”

I told you that usually we teach that you say what you are going to do, you announce it beforehand, for example, “I will now go around you and touch your feet,” and you say that before you do it. Of course if you are fluidly working and experienced, you might be able to skip it because you know the person is in touch with you. But if you’re not, you better do it, you better do more of this careful preparation, until you learn it, and then…because your interventions need to be decisive. You know, you cannot do it like, if I say “I am going to touch you,” and I do it like this [modeling an ambivalent, hesitant reaching out to touch the other person]. Then you get a negative response!

Applebaum: So what you’re modeling is the difference between actually making contact with someone physically and reaching out tentatively, where the hesitation is communicated, not the contact?

Elsaesser: Exactly. So the learning is that you are ready to make an error. “I do it,” and then I get a response, “its not right,” OK then I need to retreat, but not hesitantly, because then you get no response. And then you can’t prove it doesn’t work.

Applebaum: So be present with whatever you’re doing and find out what the response is?

Elsaesser: Yes. So another element is that our focus is not to go very fast—it is a teaching process that goes to weeks, every day, change. So how to stay in contact? Sometimes you can establish one, but it fades out, how can I stay? It is a kind of endurance, it is also an inner attitude. There’s not much happening, and I stay with you, I go through the boredom. You might be in a coma state, and bored! And even if things aren’t dramatic—OK, you stay with that, and you have endurance.

Applebaum: So if you gain a sense that the person in the coma is bored, then your job is to be present to them during that, for a period of time, which requires endurance and self-awareness.

Elsaesser: Yes. So it is always appreciating the state that the person is in, and then observing that your interventions something might happen.

Applebaum: So its not just about “doing something to” the person so that a change might occur.

Elsaesser: Exactly. You see this is why in the training we also conduct three days of contemplation training. The people imagine themselves as being in coma…you go in the unknown yourself, you don’t know what is there. When we started the meditation training, people were immediately enthusiastic about it, they says “Yes, this is needed!” it can be that at one stage you sit one and a half hours with a person, just in contemplation, and relate yourself to the person while you are in a state of meditation. You learn that, to be “outside of time”. You know, they are there twenty-four hours day and night. Sometimes there is always light, because its a survival thing and you can be there for some time, so you get in tune with that…this also refines your own instrument of perception.

Applebaum: So adapting yourself to the relational heeds of the other, and slowing down, or being available for an entirely different experience of time, is required?

Elsaesser: Yes. Sometimes this person in coma may be more advanced than I am: what is it that he teaches me? We can use this as a focus. It changes your perspective! If you have that focus you have a completely different experience! You see, we try not to be one-sided. Sometimes we tell the person being trained: go there, visit, get in contact, and then look—how is it that this poor person is teaching me something? And then, as a trainee, you can get a completely different response. So you can see this and of course we also consider where the patient is, spiritually, in that moment? So you have to change your own ways, question them, then be receptive again, and then also of course to see where it is good that you act, deliberately?

Of course we also experiment with things like finding out what kinds of songs the person loved, maybe not talk but instead sing to them, relate like this, and very moving things can happen. As a worker in this field you should learn to get in contact with what the person loved, but you should also find out what is the person’s medical situation: before you go to the patient, you go to the nurse, you go to the doctor, and you ask every medical question, so you have to be interested in the medical science of the situation, to understand what is the person’s condition now, what are they [the doctors] up to, where do they want to get to in treatment with the patient, what the prognosis is, and then you can sense what they [the medical treators] think and feel…and they sometimes express their insecurity if you are really interested in it. And they experience your interest, they may also want to know what your experience is, so you get in touch with the medical field.

Another focus for us is perceiving the “field”—what happens around that person in coma. Then of course you find out who is behind that patient; for example, if they say “nobody ever visits that patient,” but then you suddenly hear that there is somebody else from the family who is always there. So you look at the whole field, that is part of the work too, and you might then find that you work with the patient’s family system.

Applebaum: So is this a working relationship with the patient over time, a long-term relationship?

Elsaesser: Not necessarily. Sometimes it is “one shot one goal”—it can be. In some intensive care units people only stay a few days; some stay a few months. So you also have to learn that one meeting can be meaningful. This is what some people skip—then think, “Oh, he’s only here today.” But you know from your own experience, I know at least, that one moment can be very decisive how a person was with you.

I remember very much when I got was in the hospital years back, I received a troubling diagnosis—shock! I went out to make a telephone call, and the doctor who made the examination was deaf, and he came after me, went out, waited while I made my telephone call, and then held my hand, and expressed some kind of compassion.

This I never will forget. It was only one moment: this guy left his being busy, he waited there until after my phone call, and this made a huge difference for me, that one moment. Its also in this work…something is timeless, its months, but sometimes the one moment is an impulse that helps you or that you never forget. You never know, you cannot say “I am doing this,” but it is a spontaneous knowledge, “Oh, this called me, and I followed it, and I am there for you in this moment.” So it is very incomplete work of course, very, because…it is not a thing like a whole course of therapy.

Applebaum: Many Americans have a very pragmatic attitude and might ask, “Well, how do you really know you that you are communicating with that person? Yes, you might feel that they are moving their hands, there might be facial changes, but how to you really know that what you’re doing is ‘working?’”

Elsaesser: Well, one approach is “evidence-based”: if you find out, and do interviews after a patient has recovered from coma, and you see that it made a difference that you were there. Or you interview the family of people that recovered—and of course not all recover—and you can see does our approach to working with the patient make sense or not? This is one thing, an “outward” approach, so to speak.

Then there is a very refined aspect of it, and I guess we have this kind of experience more or less on an everyday basis—we might telephone each other and I say something and there is a silence, on your side, and then I might ask, “Are you still there?” Or I might feel, “Yes, he is there.” And I might ask, “You got me?” and you say, “Yes.” Of course, you confirm, but even through a telephone you can have a felt sense that we are connected, or alternatively, that I lost you.

Applebaum: So in everyday life there are already experiences of recognizing whether someone is present with you or absent, if they drop off, with or without words?

Elsaesser: Yes. You see I would say this coma work is only a sort of magnifying glass for everyday experience and because you cannot ask right away, “You got it?” with a patient in coma, there is something in that sense “missing.” But in our everyday life we more or less know, sometimes, and sometimes we need to confirm, and we sometimes confirm only because if we do not, we would know. So there is something about this and also you can see sometimes when you work with people from day to day, that the contact changes qualitatively—you observe it.

It is not always the same—of course you can say that the person is improving for any number of other reasons. Sometimes you feel that the inverse happens: you are having a very good contact with the other, and then you don’t reach the person anymore. And then you have to broaden your—this is where multi-professional work comes in—if I feel I “lose” the person, I would right away go to the nurse to ask what is happening medically, what do you feel about it, what has been done, has something changed from your perspective, and you have a counsel around it, and then you see–“Aha!”

It is interesting that in a team that works well, which is not always the case, because there are a lot of prejudices also, but it makes a big jump. Its like…I worked in psychiatry, then you also have a patient and you talk about it, and…Aha! Everybody has a facet of the perception of what’s occurring with the patient and so you can see you are only one, you are not “The One” who says “this is going on with the patient,” you are part of a team.

Applebaum: Similar to the way we recognize responsiveness in everyday life, in your training, do you list different things to watch for or to be aware of in the other, in order to recognize his or her responsiveness, without overly formalizing these categories?

Elsaesser: Yes. We give steps or focus. You can observe in the teaching process to understand we give some rules of thumb. But in the training we give different focus, where you put your attention. So you train the attention like what do I look, how do I include my own feeling? What is my outward observation, where do I include the field, where I look at some unexpected happenings? What observing what process is hidden and wants to unfold? So you look at the obvious, I think that is a very big step, to look at the obvious, to really look at what is really all there? Because we very often look for what is behind [appearances] and so on, but we sometimes forget to just perceive what is there.

Applebaum: So what’s evident…this person is nearly naked, the room is not too warm, there are tubes sticking out of them, no one is talking to them…

Elsaesser: Yes, it’s very important! So I ask them also sometimes like to come like an anthropologist in a foreign country, look at what is there, then you suddenly see what is there…and really to train your beginner’s mind to ask what is there? All new. Also sometimes you don’t see many changes with the person, of course, and people would say, “nothing is happening!” but then to come there with openness, you have to come new with a new inner sense.

Applebaum: So you can’t come in with preconceptions?

Elsaesser: Of course you could, but all the others do that already! So why do that again? (laughter)

Applebaum: Who have you trained in this approach?

Elsaesser: In the beginning we did it with the pastoral field. Then we discovered how important the interdisciplinary approach is, that you work with a whole enterprise, you work with the whole, and I felt also it would be a pity to have it only for pastors, so we opened it in an interdisciplinary way, and it became really rich and so people came in, some nurses, some few medical doctors, also physiotherapists. The only criterion we imposed is that you already have the opportunity to work with this sort of people—not necessarily intensive care units, we also accepted people who worked with people in late-stage dementia, or accompanying the dying. But somehow people have to have a field of practice, because it has to be applied right away.

Applebaum: How would you like to develop this work further?

Elsaesser: I guess there is something waking up in society that we cannot exclude these states and its not just a repair station, it is a world in itself that like it’s a modern way of involuntary initiation into something unknown. So I guess the aim is a broader consciousness about this, and also to open up the space opens for communication within this field and in an interdisciplinary way, from different angles, to share perceptions, and determine where the person can and should go, what you can support? And in fact I feel it is much more than just doing this work, but to broaden this work in society, and awareness of it.

Photo credits

Sebastian Elsaesser: photo by Marc Applebaum

Patient in ICU: Matt Westervelt via photo pin cc

Patient with head wound: ballookey via photo pin cc

ICU monitor: quinn.anya via photo pin cc

Hospital hallway 1: Julie70 via photo pin cc

Hospital hallway 2: Frenkieb via photo pin cc

Follow

Follow email

email

This interview meant a lot to me. Thank you. I wanted to share with you what happened with my mother before she died recently, that it was an instance of ‘visiting her’, of communicating with her at a different, fundamental level. I knew she knew I was there even when she was in a state similar to a coma.

She was in the last stages of Alzheimer, which is not too different from a coma. She was lying in bed (couldn’t walk any longer), refused to eat, and refused tubes, and was just in a different world, a world of her own, a dream world, like Sebastian said. She seemed to look ahead at something, see something that we couldn’t see. She at one point said: (they )came to get me, (to take me) to God. Words in parentheses are mine. After that she couldn’t really talk anymore, she constantly opened her arms wide as if she is praying and murmured – no discernible words. Her eyes were glazed. I just sat with her quietly, did some meditation, every once in a while, I would say a few words expressing love, and that I was there for her. She would sometimes smile, and then fall back into her distant glance. She may not have known who I was but she definitely knew someone who loved her was there. I ‘visited her’ for a week in a similar way that Sebastian describes. The day I left Izmir, I said good bye to her, and she squeezed my hand goodbye. She died the next day.

I congratulate Marc Applebaum for writing this excellent interview/article about Dr. Sebastian Elsaesser’s work–extremely enlightening–something ‘everyone’ should read! I am a philosopher with expertise in “brain death” . The article touches upon some of the critical elements I emphasized and expounded on in my recent thesis that focused exclusively on “brain death”, permanent coma, and persistent vegetative state; and that these states ‘are not’ death of the human person. And I hope that ALL the researchers (in various fields) who work in the area of human consciousness and ‘personhood’ will continue to produce more information for the public to read.

Karin Susan Fester