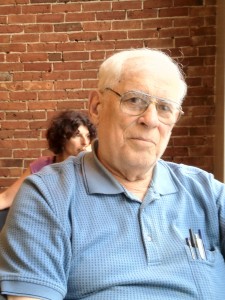

Amedeo Giorgi: A Life in Phenomenology

Jul 16th, 2012 | By Marc Applebaum | Category: Human Science In August 2011 Amedeo Giorgi was interviewed at Saybrook’s graduate conference on themes related to his life’s work in phenomenological psychological research. The panel was comprised of four former doctoral students of Giorgi’s at Saybrook: Drs. Lisa K. Mastain, Adrienne Murphy, and Sophia Reinders, and was moderated by Marc Applebaum. This transcript was edited by Amedeo Giorgi and Marc Applebaum.

In August 2011 Amedeo Giorgi was interviewed at Saybrook’s graduate conference on themes related to his life’s work in phenomenological psychological research. The panel was comprised of four former doctoral students of Giorgi’s at Saybrook: Drs. Lisa K. Mastain, Adrienne Murphy, and Sophia Reinders, and was moderated by Marc Applebaum. This transcript was edited by Amedeo Giorgi and Marc Applebaum.

Murphy: What would you say has been your greatest professional achievement?

Giorgi: I guess I have to say it is the method I developed, and I had to develop a method because my first assignment as a phenomenologist was at Duquesne University. Most of the faculty—or all of the faculty—were clinicians, and there was no researcher. So my background is in psychophysics, and natural science psychology, my doctoral dissertation was on vision, my Masters was as well, because when I was a graduate student, over half a century ago, there were no alternatives!

In the 1950’s—humanistic psychology came out in the 1960’s—if you went into psychology, you got natural scientific psychology. I happened to go to a school that had a strong research tradition—there was a clinical program [at my school], but it wasn’t as strong, the prestigious program was the research program, and I went into that program

And with that background, then, Duquesne University was starting its doctoral program: the idea was it was going to be a program purely from an existential-phenomenological perspective. Adrian Van Kaam, who was the founder of the program—he was a Dutchman—who gots exposed to phenomenology in Europe and then emigrated to the US, got his PhD at Case Western Reserve, and the way he put it to me was that he was “shocked” at the state of American psychology, that what was happening, Europe was already integrating a lot of phenomenology, so what he said was that Duquesne University had an undergraduate program but no graduate program, it was open, so he said “Let’s do one thing and do it well, and our perspective is existential phenomenology, and that’s all we’ll do, but for all of psychology, not [just] one field.”

So they needed a researcher and when I met Van Kaam he asked me—he was taking Maslow’s placed at Brandeis for one semester—and I was working at the time for a consulting firm called Dunlap & Associates in Stamford, Connecticut and I was going to Raytheon at least once a week and Raytheon was near Brandeis in Waltham, and so Van Kaam and I went to dinner one night and that’s where I really heard about phenomenology for the first time—post-PhD, because I didn’t get it at all during my training.

And I remember asking him, “If I become a phenomenologist, will I have to become a clinician?” And he said, “No, no, you can become a researcher.” And he gave me the names of European phenomenological researchers: Buytendijk, and Linschoten, and Carl Graumann in Germany, and so I realized there was a kind of tradition doing research and phenomenology, and then he said to me, “You know you’re really quite lucky you’re in New York, and you should go down to the New School for Social Research because there are a lot of émigrés from Europe who are teaching phenomenology. And so I took courses actually from Rollo May, at that time, he was teaching there, and Paul Tillich was giving a course, and the philosopher Aron Gurwitsch was also there, and so I met these people, and began reading in phenomenology, and the more I read the more I liked.

And I kind of had a professional crisis, because I didn’t believe I could project over the next twenty five or thirty years  teaching standard psychology. And I didn’t know what to do, because I was trained in this: I couldn’t go into business, I wasn’t a business type, and I was really at a loss when I met Van Kaam—he told me about phenomenology. The more I read, the more I liked. So he invited me to come to Duquesne University to develop a research method that would be compatible with the existential-phenomenological perspective that existed at Duquesne. I started…so I went there, of course I had to develop a method that was general enough and comprehensive enough, to study any kind of problem. Most of the faculty, most of the students, were clinicians, so I anticipated that many of the problems would be dealing with clinical sorts of problems, so I started to work with the method, trying to develop a method.

teaching standard psychology. And I didn’t know what to do, because I was trained in this: I couldn’t go into business, I wasn’t a business type, and I was really at a loss when I met Van Kaam—he told me about phenomenology. The more I read, the more I liked. So he invited me to come to Duquesne University to develop a research method that would be compatible with the existential-phenomenological perspective that existed at Duquesne. I started…so I went there, of course I had to develop a method that was general enough and comprehensive enough, to study any kind of problem. Most of the faculty, most of the students, were clinicians, so I anticipated that many of the problems would be dealing with clinical sorts of problems, so I started to work with the method, trying to develop a method.

Of course when I went there my knowledge of phenomenology was very limited, very slim, but the big advantage of Duquesne, and I haven’t seen this exist again, was that the philosophy department was existential-phenomenological, there were ten or twelve existential phenomenologists, so what I did, every semester when I was teaching phenomenology I also was studying phenomenology. So I was very privileged because I got Husserl from John Scanlon, an excellent phenomenological scholar—I once had a scholar say, “If you have a question about what Husserl would say, ask Scanlon, because he’s just like Husserl!” So I got a really good introduction…I got Merleau-Ponty from John Sallis, who is a very well-known scholar, he’s at Boston College today, and I also got Merleau-Ponty from Al Lingis—Lingis is the translator of Le Visible et L’Invisible, The Visible and the Invisible, that French work…so, high class philosophers teaching philosophy, and I had to translate that into psychology: what are the implications of this philosophy for psychology? What would be valuable for me to carry over here to psychology?

So that was a kind of big effort during those years, and as I said, we also had European visitors…from Europe, and Stephan Strasser came over from Holland, Paul Ricoeur gave a course, Remy Kwant, another Merleau-Ponty scholar, and there was also a summer course, so for twenty-five years I sat in philosophy courses. And after I knew some of them, I just kept taking them, and I had courses in Kierkegaard, and Gurwitsch, and Scheler, Merleau-Ponty, Heidegger…so I really built up a background. And then the point was: out of all of this background, what’s valuable for psychology? And for me of course, general psychology, not being a clinician, I wanted to know how these ideas could be transported? My primary responsibility was methodology—I had to get a method developed. So I started in the early years—the doctoral program started in 1962—so the first dissertations didn’t come out until about ’67, ’68.

In 1969 I had a sabbatical coming. So I went to Denmark to spend a semester and a summer there, because there was a Copenhagen School of phenomenology—you know, Edgar Rubin was there, you know he is famous for the figure/ground [distinction in psychology], and he was always in competition with David Katz at Rostock. Anyway, this was in ’69, and this is when the student revolts were all taking place. The Copenhagen people said, “you know, we’d love to have you, but there’s absolutely not space, we’re so overcrowded in psychology! But, there’s a brand new department in the University at Aarhus”—it’s a university on the peninsula attached to Germany there—it’s the second largest city—he said, “If you go there, then you can visit with us any time, but it’s a brand new department, with plenty of space.”

So they did invite me, and I spent a year at Aarhus, commuting to Copenhagen. And Rubin had died before I got there…the Chair was a man named Edgar Tranekjaer Rasmussen, and another one, Ib Kristian Moustgaard, and From, these were the three phenomenologists—so I had many conversations with them, learned what the Copenhagen School was about. But the main thing I wanted to do was to track down all of the main European phenomenologists who were doing research: I went to every country in Western Europe, you know—France, England, Germany, Holland, Belgium…every time I would meet [with them] I would ask, “who is doing phenomenological work?” Plus, Van Kaam said to me, when I first went to Duquesne, “In Europe there are research phenomenologists and they are using a method.”

Now, I’m trying to develop a method [at that time], but I’m saying, if there’s a method already in existence, why don’t I, you know, get a hold of that? Well, every person I went to, not a single one had a method: what phenomenology meant to them was a critique of mainstream psychology, but with no constructive alternative. So after these nine months in Europe, smoking out every phenomenological psychologist that I could find, I’m still empty-handed!

Now, I’m trying to develop a method [at that time], but I’m saying, if there’s a method already in existence, why don’t I, you know, get a hold of that? Well, every person I went to, not a single one had a method: what phenomenology meant to them was a critique of mainstream psychology, but with no constructive alternative. So after these nine months in Europe, smoking out every phenomenological psychologist that I could find, I’m still empty-handed!

But—I guess maybe its part of the American character—I felt, well, do something about it! If you don’t see what you want, create something! So I developed a method, I came back, and I said, “Well, I’m going to develop a phenomenological method.” And I introduced a new course [at Duquesne] called Phenomenological Method, there were about eight students in the seminar, and I said, “I don’t know what I’m going to teach you [laughter], I know that I read Husserl, who said you have to describe, you have to go back to description.” So that semester—it was 1970—was the first time I taught the method, and of course over each semester I kept repeating it, and I modified it, and I kept the course going.

And I would say developing a method where there was a vacuum probably is the biggest thing, and probably I would almost say “too big,” because it has dominated my life [laughter]. I didn’t mean for method to take such a role in my life—people heard there was this method, and they wanted me to teach a workshop, or go and teach. And my idea was to meet…the task: Duquesne wanted me to go there and develop a method, OK, I wanted to satisfy that criterion, but then I wanted to go on to write books about phenomenological psychology itself. So, after fifty years of doing method, I’m tired! I want to get on to a book on Merleau-Ponty, a book on Husserl, where I get into the substance of phenomenological psychology, not just the method. It has been a good thing, but also a distraction, in the sense that I couldn’t let go of method, that’s where everybody was pulling me, toward the method. So I hope at this old age to write books on substantive phenomenological psychology, what that means and why that would be important for psychology. So that’s a long answer to your question, I wanted to give you some context why I thought that method was so important.

Reinders: how would you describe the essence of the method that you created?

Giorgi: Well, the essence of the method is looking for essences [laughter]. It is a search for essences…because I come from that natural science background, I really learned science and I appreciate it very much, and I don’t want to throw away science—I want to keep science in the picture. Now a lot of people think that because for years phenomenology was criticizing [empirical] scientific approaches, they were really criticizing the monopoly it had, not the scientific method itself. So it kind of got a bad reputation, as if, if you’re a phenomenologist, you’re anti-science. But anybody who reads Husserl cannot get that impression. He’s a tough read, and if you read him, you appreciate science, and so—one of his works is Philosophy as a Rigorous Science, huh? So this was the idea that Husserl was trying to pursue.

But its nothing like natural sciences as such, because its [dealing with] human experiences and human phenomena. So I want to be sure that our criteria is this: that every natural scientist will have to respect our method. I’m not just trying to satisfy clinicians, or therapists, or humanists, I’m trying to satisfy the most severe criterion—natural scientists. And so they have to respect my method, because I anticipate that some day, when qualitative research develops and gets strong, the natural science people are going to criticize it. And I want to be able to stand up and say, “Go ahead, criticize it—but you won’t find any flaws here.”

So that was the criterion that I always had, and the funny thing is, every time I go to APA—I went to APA for twenty-five  straight years, before I gave up!—I went because I wanted to dialogue with mainstream psychologists, with the research psychologists, you know, who I was trained with. And while I was easily invited to give papers with Division 24, Philosophical, or 32, which is Humanistic, or Historical—I would go there, but all my friends come there [not the others]! So I was really trying hard to do Division 3, Experimental Psychology, because I wanted them to accept a qualitative [alternative]. One year they did, so at last, you know, I prepared a paper speaking to all of these experimentalists, explaining that phenomenology was equal to science…and all my friends showed up! [laughter] What happens is, the other side never comes! So I thought, “Well, I give up!”

straight years, before I gave up!—I went because I wanted to dialogue with mainstream psychologists, with the research psychologists, you know, who I was trained with. And while I was easily invited to give papers with Division 24, Philosophical, or 32, which is Humanistic, or Historical—I would go there, but all my friends come there [not the others]! So I was really trying hard to do Division 3, Experimental Psychology, because I wanted them to accept a qualitative [alternative]. One year they did, so at last, you know, I prepared a paper speaking to all of these experimentalists, explaining that phenomenology was equal to science…and all my friends showed up! [laughter] What happens is, the other side never comes! So I thought, “Well, I give up!”

But anyway, the essence of the method is the discovery of essences through the method of free imaginative variation. I would say that’s what we do, we try to come up with the essences. But of course in psychology—it’s a psychological essence, not a philosophical essence. And that makes it a little trickier of course because [historically] we don’t know what psychology is yet—it is not yet an historical achievement what “psychology” means. Nevertheless, I go ahead and do that—that’s what I would call the essence of the method.

Murphy re: can you contrast your approach versus that currently being employed at Duquesne, which focuses on identifying themes rather than essence?

Giorgi: Well, first of all a lot of people who call themselves “phenomenologists” [instead] come up with thematic analyses. Thematic analysis is not really phenomenological: they confuse the difference between the constituents of a structure. The difference is, the constituents are interrelated—Husserl makes a distinction among parts between what he calls “pieces” and “moments.” A “piece” is a part that can be independent of the whole: I can break a branch off a tree; the branch becomes a piece. But then there are parts that you cannot separate, and he calls them “moments,” so that the color green of a leaf is a moment—I can’t take green out of the leaf, OK? It belongs to it. So a constituent is a moment of a structure, it is quite different, it is interdependent with all of the other moments, it can’t stand alone like a piece.

Thematic analyses are like pieces, people do these analyses as if they were independent, and they get separate—they get six themes, or eight themes, but what’s the relationship between the themes is often not spoken to. And if anything, phenomenology is very holistic, it is sensitive to the whole. And so to do a thematic analysis and leave the themes independent is not satisfactory, at least according to phenomenological criteria.

Now, if you have other criteria, it may be OK, but you’re really an empiricist—you know, like if you’re doing Grounded Theory, and you come up with the various themes, that’s OK because they are following empirical philosophy, not phenomenological philosophy. But we want to come up with an interdependent understanding of the parts, the moments, so I would say that if the Duquesne people have gone in that direction, they’re departing from phenomenology, in the strict sense, because its not phenomenologically qualitative.

Murphy: Might this be an effort to bridge with empiricists?

Giorgi: Well, I think they just don’t know phenomenology well enough—you certainly don’t undermine your own process in order to communicate. You have to communicate being faithful or integral to your own procedures and your own processes, and then you try to do communication, but if you undermine your own process in order to communicate, then its just…then you’re not communicating.

Applebaum: sometimes students who are learning the descriptive method think they can vary or add steps to the method, how would you respond to that?

Applebaum: sometimes students who are learning the descriptive method think they can vary or add steps to the method, how would you respond to that?

Giorgi: I encounter it all the time! I don’t know what it is, but there’s something about not fully appreciating what a method is and what a method means, and what a method can do. I’m often accused of being a purist, you know? I mean, “Oh, you have that method and you just hold to it!” Well, let me give you a simple example: how much is five plus five?

Applebaum: Ten…as far as I know!

Giorgi: Ten? It can’t be eleven? Or maybe nine, can it be nine sometimes? You mean five plus five is always ten? What are you, a purist? [laughter] In other words, there is a logic to methodology. In my method I’m not doing what I want to do, I’m doing what’s demanded of me by the method, so that, if there are certain steps there, there’s a logic behind all the steps, among the connections between the steps, it’s not me, it’s the logic, I’m following the logic of phenomenology in having these certain steps. But students…I think its because sometimes you mingle theories, they mingle theories a lot, and I do find students who sometimes say…you know Saybrook has a requirement that as part of candidacy you critique a dissertation, and I always have them critique a dissertation done elsewhere, because you’ll have a lot more to say, so if you picked a Duquesne dissertation that I directed you might not have much to say.

So what I get are students who might say, “I used a little bit of Moustakas, and a little bit of Colaizzi, and van Manen, and I did this step….” You can’t mingle steps like that, there’s a logical structure, you have to stick to the method, that’s a requirement, that’s a demand. You can change maybe with theories, you can say, “Well, I took a little from Jung, a little from Freud, a little from Adler, you know I’ve come up with my own theory.” That’s maybe a little bit more defensible, but you can’t do that with methods. They are logical structures, there’s a logic, there’s a structure to it.

Now, what maybe makes phenomenological method it more difficult may be that I follow the phenomenological criteria, but I also follow the criteria for good scientific practice—and you have to know science as well. What does science demand? What does phenomenology demand? Therefore integrating those two can be tricky if you’re not well steeped in both traditions, the scientific tradition and the phenomenological tradition, but I clam to be able to meet both criteria. I always say the method is both good science and good phenomenology, and I articulate that logic, I take on all the critics, and I say “look, this is why,” and I spell it out, and I have never received criticism on that, so far: maybe it might come, but so far I haven’t. So the point is you don’t play with methods the way—maybe—you can play with theories. Methods are strict like logic, its like suppose you had students who had trouble with the analysis of variance? Do you change the formula so that the student can do it more easily? No, [if you’re the student] you say, “I have to come up to understanding the formula.” It’s the same with phenomenology, you say, “I have to understand these steps, and I’ve got to implement these steps.

And I say this because some qualitative researchers seem to say in their work, “if you think you have a better step than the ones I’ve proposed, go ahead, do it.” But then that’s not a method—flexibility is good, there can be flexibility of a certain type, but not any kind of flexibility. So I’m a little worried that if the so-called “mainstream” [psychological] people start looking at these sorts of qualitative research, it will be bad for the qualitative movement. You’ve got to have high standards: you’ve got to do the best. So if you want to learn something, you can’t casually mix methods, you have to pick a method.

Now you might do some little variation [on the method you’re using] but you’ve got to justify it. If you modify a method, you’ve got to justify it—its got to be logically consistent with all the other steps of the method. So I would say no, you can’t modify methods at will.

Mastain: If so many students are adding these steps, clearly they’re having a problem with the method…so what do you  see as the most difficult aspect of teaching this method to students, that students are struggling with?

see as the most difficult aspect of teaching this method to students, that students are struggling with?

Giorgi: Well first of all, have you ever encountered students struggling with statistics? I have. The fact that students are struggling with the method is not a new phenomenon, that’s all, its part of training. Now in my aim the hardest part is getting the structure, moving from the third transformation. That’s always—because it’s an intuitive process, and by “intuitive” I don’t mean in the everyday sense, I mean in the phenomenological sense. You’ve got to be able, through imaginative variation, to see what’s genuinely essential, it’s a process, it’s a “seeing.”

I have also learned that sometimes, because people are having such a difficult time, to say, “Tell me what’s the last movie you saw? Tell me about it, quickly.” And then they’ll tell me, “Well, it was a mystery about such and such,” and I’ll say, “Well, that’s what you do to get the structure.” You’re giving me the essence of a plot. And I say, “Now, what did you do [just now]?” And its hard to do it and describe it. When I try to describe it I don’t do it well, so I have to bracket describing it, and do it—so then when I do it and show the outcome, most students will say, “OK, now I see it.” Well, how did I do it? I ask myself the question, “What is truly essential about this phenomenon?” I have the data here, you know, and I have to go through, but you know, I come up with it.

Now part of the problem is, I deal with is I often have students without sufficient background in phenomenology—you don’t get exposed to it. So the more you’re exposed to philosophical phenomenology, the easier the task becomes.

Secondly, you’re also invited to do a truly original, creative task. Nobody has ever done this before—psychologically. There are philosophical examples. Then you have to struggle with, “What do I mean by ‘psychological’?” As I’ve said, there’s no historical answer to that yet that’s agreeable to the community of psychologists. I’ve come up with that in my own sense—that it’s the subjective meaning that we attribute to things. What is the subjective meaning of this experience, for you? But you also have to say “psychologically subjective,” because “subjective” is larger than just the psychological.

Then you have to come up with an insight, once you have the right framework. Nobody has ever done that before. And if you have a different phenomenon, then you have no history—its not that I can give you, “Well, read Wundt, he’ll give you…”—no, Wundt doesn’t do it, or “read Freud”—no, Freud doesn’t do it…you can’t read anybody, you’ve got to do it without reading. That makes it difficult—it’s a new, creative task. Well, should we not try it then, because nobody’s ever done it? I don’t think science works like that—even if it’s difficult, scientists say, “Well, try the task.” So every student who does a phenomenological dissertation is creating something that never existed before, if you’ve done it right. Then you have to reflect on that, and say “What did I do, how did I get there? Can I articulate that for somebody else?” And get it done. So it is genuinely new.

You know if you really want to be a scientist working at the forward edge of things, then do a phenomenological dissertation on a phenomenon that nobody has ever worked on, and come up with the psychological essence of it. There’s no place but other dissertations that I can tell you to read [for examples] but they’re usually different phenomena. So I say, that’s why that is so difficult.

Reinders: Can you speak a bit about validity and reliability in phenomenological research—this is an issue that often comes up in my work with graduate students.

Giorgi: Well, it is so simple in a phenomenological way, but everybody doubts it or doesn’t believe it. You know part of Husserl’s theory of meaning—there’s a threefold process. There is what he calls the empty meaning—what’s the technical word, I always forget that word…

Applebaum: [The intuition is] “unfulfilled.”

Giorgi: Yes its unfulfilled but that’s not the word itself…you search for a meaning, then there is a fulfillment. You see something that may or may not fulfill what started the search for the meaning. And if it meets the criteria of the empty search, then you have identification. When you have identification, you have validity—if you do it twice you have reliability. I always give this example, “Where did I put my glasses?” That’s true enough for me anyway, I leave them on…so I’m searching for my glasses and somebody sees me, “What are you doing?” “I’m searching for my glasses.” That’s the meaning—its empty because I’m searching. Then, if I look around the room and see some glasses, it’s a kind of fulfillment—“there are glasses.” But wait, they’re not my glasses. It looks [at first] as if they could fulfill, but eventually I have to say “No, they’re not my glasses.” Then if I find my glasses, then good, I can now see well. What triggered off the search was a kind of empty meaning, I had a kind of quasi-fulfillment, but they weren’t identifications, [then] I got the glasses, I have identified.

Giorgi: Yes its unfulfilled but that’s not the word itself…you search for a meaning, then there is a fulfillment. You see something that may or may not fulfill what started the search for the meaning. And if it meets the criteria of the empty search, then you have identification. When you have identification, you have validity—if you do it twice you have reliability. I always give this example, “Where did I put my glasses?” That’s true enough for me anyway, I leave them on…so I’m searching for my glasses and somebody sees me, “What are you doing?” “I’m searching for my glasses.” That’s the meaning—its empty because I’m searching. Then, if I look around the room and see some glasses, it’s a kind of fulfillment—“there are glasses.” But wait, they’re not my glasses. It looks [at first] as if they could fulfill, but eventually I have to say “No, they’re not my glasses.” Then if I find my glasses, then good, I can now see well. What triggered off the search was a kind of empty meaning, I had a kind of quasi-fulfillment, but they weren’t identifications, [then] I got the glasses, I have identified.

For Husserl, that’s validity, because the fulfillment [of the intuition] satisfies precisely the meaning that started off the search. And if you do it twice or more, its reliability. So some people think its too subjective or too individualistic, or I don’t know, too easy, but you see phenomenology trusts individual experiences—with a critical perspective of course: you have to evaluate it, criticize it, which you do when you go from quasi fulfillment to the kind of fulfillment that you call an identification. So that’s reliability and validity from a phenomenological perspective: it’s all in Husserl, it’s all right there.

Murphy: I believe the term [you were looking for earlier] is “signifying”…

Giorgi: Signifying, yes—the first search in meaning is signifying, it’s a way of understanding my [seemingly] random activity, looking over tables, chairs, it’s a signifying intention, then a possibly fulfilling intention, then identification: signifying, fulfilling, identification. Now, his theory of meaning is more complicated than that, but I’m pulling out the one side [of Husserl’s theory] where he says it’s the same as validity.

What’s validity? Well, will this test really measure anxiety? Is this test really going to fulfill the intention I had? I had the intention of finding out how anxious this person is, I’m going to give this test to them, I come up with a score, did that score really fulfill the intention I had? How well does it do it or not do it? That would be the identification. But of course at the empirical level its never perfect, you get quasi-fulfillments, probably, not true identification.

Reinders: Would you speak a little bit about the realm of areas in which phenomenology can be relevant beyond formal research?

Giorgi: Well I can say “anything experiential.” If you can experience it and you can describe it, you can do a phenomenological analysis of it. Those of you who have worked with me know, I never dictate the phenomenon you’re going to work with. Its hard enough to do a dissertation that you better like the phenomenon at least, because the process is long enough! So over the years as long as I have directed dissertations I have never dictated the phenomenon, I have let the student choose it, then I have helped them with the research.

Well I have gotten everything…in one sense its bad because I’m not building blocks of psychological knowledge that I’m interested in, but on the other hand I have a lot of happy students who study what they’re interested in: so I have, well, Adrienne [Murphy] was with breast-feeding, Sophia [Reinders] was with artistic creation, Lisa [Mastain] was with altruism, Dennis [Rebello] is working with telling life-stories, I’ve had nurses do it—if it is experiential, and you can describe it, you can analyze it. That’s the beauty of phenomenology, it has a tremendous range.

Mastain: Do you think you have to be a [philosophical] phenomenologist to do this, to get it…to read Husserl, et cetera—because there are lots of people who would like to get to the essence without doing all that reading!

Giorgi: Well, obviously the more philosophy you read the easier the process, the better the understanding, the better the free imaginative variation, the better the intuition, so I can never say “Don’t read the philosophers.” The question is, how much do you have to read in order to do reasonably good work? When I was at Duquesne I was very lucky because the philosophy department was phenomenologists and any psychology student could take philosophy courses and have them count toward the degree. So our students would get say over six semesters, six philosophy courses in addition to the phenomenology that we worked into our own [psychological] lectures. So they were pretty good, they were in really well-grounded, they were good, they had great background.

When students have less background, the opportunities are not there to the same extent. So in the workshop course I give you the absolute minimum conceptual analysis of the philosophy on day one, but I always say: “Read! Go back, and read!” And I give you good secondary authors, so that you don’t always have to go to Husserl, like Zahavi, or Mohanty, you know, people like that who are good, and you can get a good sense of phenomenology from them, shoring up, you know, your background so that your praxis will be better.

The official title of that course is “The Theory and Practice of Phenomenological Psychology.” The theory and practice. If you only practice and you don’t know theory, you won’t do well. And if you only have theory and you don’t practice, that’s not so good either. It’s both. So how can you get both? Well, if I catch a student early and can work with them over six years or seven years, they get good grounding, because there is the opportunity and the time to do that. If I get a student, and they have all their coursework done, they’re at the practicum level, and then they want to do phenomenology, I kind of respond [cautiously] like, “Well, let’s talk about this” because I think you ought to have at least three courses before I will even let you do that, if its possible at all. So the answer to your question is, it’s not good to have no philosophy, I can’t argue for that, but I can argue for at least limited philosophy sufficient for you to do good phenomenological psychology.

And the other problem is it has to be interpreted correctly—reading Husserl can be off–putting…he’s very rigorous, very good, but he’s writing for 19th century people, and unless you know the philosophical problems of the 19th century, you don’t know exactly where he’s going, so you need guidance—in what sections to read, what sections to drop. Merleau-Ponty is far more user-friendly, because he knew psychology better, so if you read Merleau-Ponty its solid stuff too, but he’s very, very much speaking to psychologists as well as philosophers.

So if you read him…Sartre, the early Sartre, is very good because he’s very psychological—the books on emotion and imagination—and then again sections of Being and Nothingness are quite good, in the descriptions of behavior, not the whole book, you need to know which sections to highlight and read. Heidegger can be very good, but he’s so involved with the question of Being, so unless you know how to back away from that a little bit, you can get lost in Heidegger as well. So it’s a matter of selecting the readings, and I find today that some secondary sources are getting better and better. I thought in my naiveté–the first generation, if I just explained to people what phenomenology was, they would just come aboard, well obviously that didn’t happen! [laughter]

And I thought maybe it needs a second generation, when that might get done, but not quite, but I think maybe with the third generation, because some of the philosophers like Zahavi, and Drummond, and some of the younger philosophers who are coming on board now, are writing it in an English idiom which is much more accessible for non-philosophers, its getting better. So I think maybe in that third generation…now I can tell people, “Read Zahavi and then do the work,” because he understands Husserl really well, but he writes well and he communicates well, so I think it took so much time because Husserl was so deep and so comprehensive…there is a new two-volume set on Husserl by Mohanty, and it is awe-inspiring to see how much Husserl accomplished. He covers Husserl’s whole life from 1890, The Philosophy of Arithmetic to…he died in 1938, and one book is called The Early Years and the other book is called The Freiburg Years..and in the Freiburg years especially, the topics he covered, the distinctions he made…its no wonder its overwhelming to non-philosophers. If you don’t know the history of philosophy, what he’s speaking to, it’s a very, very hard read. We need someone to interpret him and make him palatable to our task.

And a lot is in there that is good for understanding science, for understanding human beings, for understanding consciousness, but its hard to get at without translations of some type. So I think the third generation might make it far more accessible to non-philosophers, but Husserl himself, as good as he is, I would say quite honestly, if I hadn’t sat in on philosophy courses at Duquesne with expert Husserlian scholars, I would not have gotten him right, on my own: I would have read him, but pulled away with the wrong thing. They were able to tell me: here’s what he’s up against, here’s the problem, here’s what he’s doing, so “Oh, now I see, “ but if I’d read it on my own, I wouldn’t have gotten it.

Applebaum: Would you say that reading phenomenology not just an intellectual challenge but an experiential challenge as well?

Giorgi: Sure, you really have to stick with it, and you really have to really understand what they’re saying—not interpret too easily, and say, “Oh, he’s saying this and he’s saying that,” because you run across a familiar word or a familiar phrase. No, you’ve got to lend yourself to their project first, then critically evaluate it. I usually try to recommend Merleau-Ponty because he’s more user-friendly for psychologists. But every mainstream psychologist to whom I said: “Read Merleau-Ponty’s Structure of Behavior if you want to get a sense of phenomenology—they never come back to me! That’s a very difficult text, and it takes time. But they never come back and dialogue with me, but its tough, and that’s the whole point—that it’s an experiential challenge as well. And it draws you seemingly away from current psychological issues, but it s a deepening of those issues, if you know how to come back to them.

Murphy: The research method is obviously central to your life’s work; how would you encourage those of our generation who have studied your work to communicate or propagate it more widely in the community? How can we contribute?

Giorgi: Well in addition to teaching it correctly to others, that would be one thing, if you have the personality and the stamina, go dialogue with mainstream [psychological] people, you know, because the ideal after all is that psychology itself has to be changed. To me it’s on the wrong track, it’s not well-founded, it’s got to get better founded and what I see in phenomenology is the proper founding of an authentic psychology. But it’s a task that’s bigger than a lifetime: it simply can’t be done by one person, by himself or herself, so I’d say that the two things are, first, teach the method to whomever is interested, teach it well and correctly, and the second thing is dialogue try to tell them that there is a qualitative method that is as rigorous as any quantitative method…

As I say this, I came across an Australian psychologist named Joel Michell who measurement in psychology, he’s a quantitative psychology, and his point is that the idea that psychological variables can be measured is an assumption and its never been proven. He’d like to be the one to prove it, but he hasn’t done so yet and he admits that. He goes back to S. S. Stevens who wrote –when I was a grad student in the 1950’s this handbook of experimental psychology came out edited by S. S. Stephens, and he wrote on measurement where there’s the ordinal scale and he [Michell] says Stevens got it wrong, he didn’t ground quantification properly, and yet fifty years of research is based on what Stevens said. And you know what’s happening to him? He’s being ignored as well. I mean, I know where his articles are, but mainstream people are going ahead doing quantitative research, they’re not responding to the critique, so if qualitative research is vulnerable, it’s kind of new, quantitative research is in no better place, he knows philosophy of math and it’s not right, its an assumption, so everyone who feels like “I’m really being scientific it has never been proven that psychological variables are accessible to quantitative procedures.

Applebaum: Another student had asked, how widely is phenomenological psychology being taught, it is being sustained today?

Giorgi: I can name the schools where it is being taught—it is being taught, it is being sustained. My view is that it will never disappear, it will never be mainstream, its going to be on the margins somewhere as far as I can envision it, I’m not with it because it is marginalized, I’m with it because I feel its true, access to that we don’t’ see yet, hit and miss, I’m not saying that all mainstream psychology is off, but sometimes the successes are incidental, resistors to mainstream.

I’m also a historian of psychology and I can demonstrate to you that in every decade since 1879 there are people who have criticized mainstream psychology, I could write a history of dissident of psychology, like people like Brentano, Politzer in France, there is a dissident history of psychology, where these people are saying that mainstream psychology is not the best way of understanding psychological phenomena and the difference between them is not as great as the difference between behaviorism and psychoanalysis–that’s a real big difference. The difference between the dissidents is not that great. So where are we going? In philosophy in America, phenomenology is strong: I just saw the schedule for SPEP, its quite strong, its good, there a lots of good young American philosophers, the generation succeeding me, good topics and papers. So I don’t think it will die, I don’t think it will be major or mainstream, I thin it will always be present as an alternative, and I think it comes down to an existential choice: do I work with mainstream people or do I work with the marginalized people? And phenomenology today is marginalized socially speaking, but not truth-wise, I think truth-wise it is seeking the essence of psychology.

Credits:

Thanks to Saybrook University for hosting the interview with Giorgi in 2011

Photos of Amedeo Giorgi courtesy of Marc Applebaum

Copenhagen photo credit: Sigfrid Lundberg via photo pin cc

Anatomical image photo credit: Curious Expeditions via photo pin cc

Stairs photo credit: toastforbrekkie via photo pin cc

Studying photo credit: beX out loud via photo pin cc

Glasses photo credit: » Zitona « via photo pin cc

This post is an abbreviated version of the extended interview first posted in three parts on The New Existentialists

Follow

Follow email

email

[…] On May 25, 2013 the philosopher J. N. Mohanty and the psychologist Amedeo Giorgi participated in a panel discussion on phenomenology as part of the annual meeting of the Interdisciplinary Coalition of North American Phenomenologists held at Ramapo College. The talk was moderated by James Morley; questioners included Louis Sass and Lester Embree. I organized and filmed the panel. This is Part One of the panel; Part Two will be posted later this week. An in-depth interview with Giorgi that I moderated in 2011 can be read here. […]

[…] An in-depth interview with Giorgi that I moderated in 2011 can be read here. […]

[…] In an interview from 2012, one of the founding fathers of using phenomenology in psychology, Amedeo Giorgi, threw the following challenge (my apologies for the long citation, but I wanted it to be unaltered and un-focused by me): […]